It was ninth massacre of the year in Honduras and a trigger for the president Chiomara Castro exploded against the Minister of Security.

“Everything that I was asked, I decided. National Control of Detention Centres, Handover of Forces Anti-Maras, Directorate of Investigation and Intelligence, Exception Status and expansion to over 60% of the country… It cannot be that we are being attacked by organized crime in constant mass killings and femicides,” he wrote on Twitter.

Secretary of Security: It cannot be that we are being attacked by organized crime, among other things, in the form of constant massacres and killings of women.

I demand decisive action and results in the next 72 hours!

The waiting time is over!

2/2— Xiomara Castro de Celaya (@XiomaraCastroZ) March 7, 2023

Honduras has been in a state of emergency since December 6, which covers more than half of its territory and restricts the rights of citizens to fight crime.

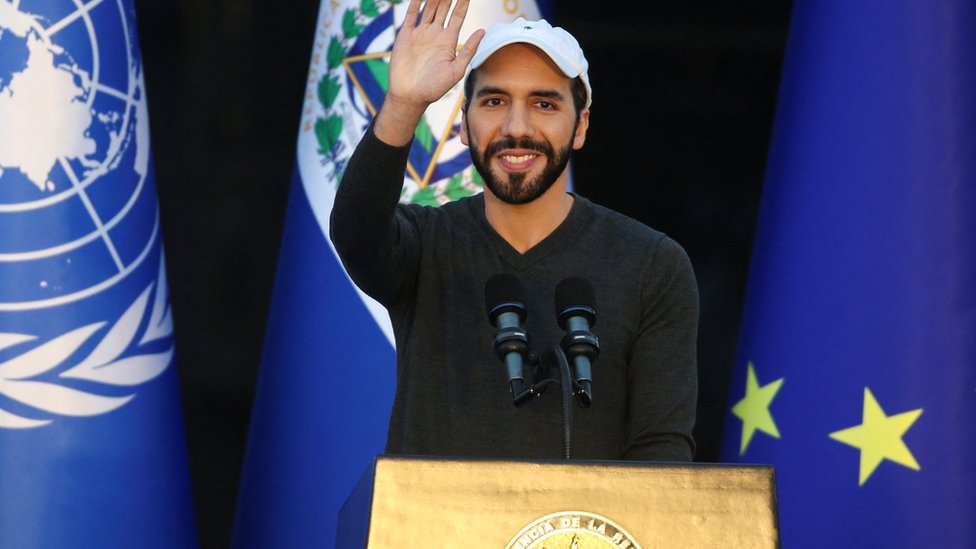

Analysts interviewed by BBC Mundo say the measure is a consequence of the “Bukele effect”, a product of El Salvador’s war against gangs.

El Salvador spent a year in dubious exclusion mode human rights organizations, but many Salvadorans welcome the decline in crime and homicide rates, according to government data.

In neighboring Honduras, violence has been one of Castro’s concerns since he took office.

In 2022, the country recorded its lowest homicide rate in 16 years, at 35 per 100,000 inhabitants, but human rights groups and analysts are questioning whether the constitutional restrictions are sustainable and are warning of the consequences of the Salvadoran experience.

extended exception state

Honduras extended the state of emergency up to two times, prompting a call for attention in late February from the United Nations, which asked that it be avoided for “prolonged use.”

The state of emergency is in effect until April 20 and covers 235 of the country’s 298 municipalities, including the capital Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, the most populous cities.

The Washington Office of Latin American Affairs (Wola, its English abbreviation) recalls that this regime suspends constitutional rights such as freedom of movement, the right of association and assembly, and the inviolability of the home.

Police say the measures allowed “to strike criminal structures that profited from the Honduran population through extortion“.

This latest crime has increased in Honduras in recent years, killing hundreds of people and leaving small and medium-sized businesses on the sidelines.

According to authorities, the state of emergency has also made it possible to identify and detain gang members who profit from other crimes such as arms and drug trafficking, car theft, murders of women and money laundering.

Police Data Encryption V over 4200 V arrested for multiple crimes. They also report seizing more than 800 firearms, 80 kg of cocaine and 1,300 kg of marijuana.

Eugenio Sosa of the National Institute of Statistics of Honduras asks “to find out if other academic and civil society organizations are doing alternative monitoring.”

“It’s good that there are other sources of official data,” he told BBC Mundo.

The National Commissioner for Human Rights in Honduras (CONADEX) pointed to “inconsistencies in the data provided by the government” and recommended that the state of emergency not be extended due to non-compliance with “international human rights standards”.

“e”perfect bukele”

El Salvador and Honduras share common borders and problems. They have one of the highest murder rates in the world and their residents suffer from endemic vulnerability.

Now they also share this “Bukele model” of fighting crime.

The “reduction in murders and extortion” reported by the El Salvadorian government “has caused governments like Honduras to try to emulate Bukele,” analyst and sociologist Leonardo Pineda told BBC Mundo.

This observation, shared by centers such as WOLA, warns of the “normalization” of this method, which uses social force and restricts rights.

“For these populations who are fed up with violence, the Bukele model is sympathetic and could become a trend that politicians will embrace with enthusiasm,” says Sosa.

Honduran analysts point to differences in how it is applied in both countries.

Sosa believes that the extension of the state of emergency in Honduras is a sign that violence is out of control.

“I also see an attempt to balance the preservation of these emergencies and the observance of human rights,” the expert says.

“This is not scorched earth in neighborhoods and houses like in El Salvador,” adds Sosa, although the Honduran media reports arbitrary detentions and irregularities in legal proceedings.

Pineda warns that many of the measures appear to be “more propaganda than action” and that many communities are not feeling the effects.

“Extortion hasn’t stopped, except in some communities where the gangs themselves seem to have decided to stop so they don’t heat up territories anymore,” Pineda says.

Both analysts note that the police are “weaker” and do not have the kind of overt support from the military that they have in El Salvador.

Collateral Damage

Pineda says that Bukele’s heavy hand is causing “the migration of gang members from El Salvador to other countries in the region, and this is beginning to be noticed in Honduras.”

“Most forensic scientists agree that when a country attacks like Bukele, and other neighbors have more flexibility, they can become a safe haven and expansion” of criminal gangs, explains Sosa.

The authorities of Honduras have also observed a “mutation” of criminal structures moving from urban to rural areas of municipalities without a state of emergency.

Although the authorities are talking about a decrease in the number of murders, Honduras is experiencing bloody weeks. There have been nine massacres in the first two months of 2023, the motives for which are unclear.

After the last one, which happened at the beginning of March, Castro gave the Minister of Security an ultimatum. stop this latest escalation of violence despite the state of emergency.

Root attack problem

Much criticism of the “Bukele model” no plan beyond emergency measures.

“What will happen when these repressive actions against human rights are put on hold unless their roots are attacked?” Pineda asks.

Ana Maria Mendez-Dardon, director of Wola for Central America, recalls that “the restriction of constitutional rights creates a huge risk of human rights violations, such as arbitrary arrests and abuse of power.”

These are just some of the criticisms of Bukele’s measures, apart from the fact that the issue has not been resolved. overcrowding V Salvadoran prisons, even with the recent construction of a mega-prison.

In Honduras, Sosa mentions that these measures should be combined with “the reduction of inequality, poverty and the reorganization of institutions to reduce organized crime at a very high level.”

“And the latter cannot be resolved by simply extraditing the former president,” Sosa says, referring to Juan Orlando Hernandez, Castro’s predecessor, extradited to the US, where he will be tried for alleged drug trafficking and possession of firearms.

remember, that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.

Source: La Opinion

Alfred Hart is an accomplished journalist known for his expert analysis and commentary on global affairs. He currently works as a writer at 24 news breaker, where he provides readers with in-depth coverage of the most pressing issues affecting the world today. With a keen insight and a deep understanding of international politics and economics, Alfred’s writing is a must-read for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the world we live in.